COVID-19 overreaction has pushed us to the tipping point

Our debt is rising and our population growth is slowing. The result will be a massive fiscal burden on taxpayers in decades to come

By Gerard Lucyshyn

By Gerard Lucyshyn

Director of research

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Caught between a rock and a hard place. This best sums up the position that Alberta’s United Conservative Party government found itself in as it announced new, stricter lockdown measures for Christmas.

The government is attempting to bend the rising curve of COVID-19 infections. Premier Jason Kenney and his most trusted ministers lined up to deliver the horrible news to Albertans.

They reassured Albertans that they didn’t reach that decision lightly and that they wholeheartedly preferred not to impose such measures, however, they believed it was necessary.

This was quite a bold announcement, especially when many Albertans were looking forward to some respite during Christmas following the past shock-and-awe year; not to mentioned the UCP’s dwindling poll number placing them behind the NDP.

Since Christmas, the government has extended the harsh measures.

The premier and each minister have clearly articulated the enormous effort, debate and struggle they went through in making such heavy-handed decisions. However, one would have thought they would realize, individually or collaboratively, that harsh measures usually have consequences and are not the way to go, regardless of the unrelenting pressure tactics from social and mainstream media.

History has taught many leaders that alarming the population leads to recursive bad public policies and nonsensical rules. Overzealous government reactionary measures cause confusion, which turns into fear and then into anger.

One example of such a lesson surrounds a quickly written book in 1968 by American biologist Paul Ehrlich. In his book, The Population Bomb, Ehrlich predicted mass world starvation and resource depletion due to overpopulation. This prediction sent well-intentioned politicians clamouring around the world to solve the impending crisis.

By the end of the 1960s, many countries around the world were experiencing large increases in life expectancy and rising fertility rates. Population growth rates were starkly increasing, feeding into the fear that an imminent population explosion would lead to resource depletion and worldwide starvation. The fear quickly manifested into government action: a global population control program.

The mission for governments around the world was to institute measures they believed were best to bend the sharp population growth curve and prevent imminent threat to mankind. Some measures to curb population growth included fines, deductions from salaries, withdrawal of maternity leave, one child per family laws and sterilization incentives.

Not unlike our political elite today, the politicians of the past were trying to keep everyone safe. The effort to bend the population growth rates appear to have paid off and have been decreasing ever since. Unfortunately, it turns out that such well-intentioned public policy measures have played a central role in a new crisis many countries now face: declining fertility rates.

Declining fertility rates and aging populations drive the fear that in the near future there will not be enough workers to pay taxes to support governments, pensions and health-care systems. Politicians are now adopting population growth incentives such as baby bonuses, child tax incentives, monthly welfare or nutritional allowances, priority housing, education, medical care, and expanded maternity benefits.

Sounds a tad recursive.

The responses to the COVID-19 pandemic saw all countries engage in similar strategy: massive spending to fight COVID-19 and the closing down of the economy. These measures have drastically reduced economic activity and tax revenues, ending 2020 with massive debt levels, record levels of unemployment and economic systems in shambles.

It’s expected that developed countries will have a median increase of their debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio around 17.5 per cent while developing countries will increase their debt-to-GDP ratios by approximately 12 per cent, and low income countries by eight per cent. These increases in debt levels will push most countries beyond what economists refer to as the tipping point.

The tipping point is where a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is at such a level that it negatively affects annual real growth. That point is estimated around 77 per cent debt-to-GDP.

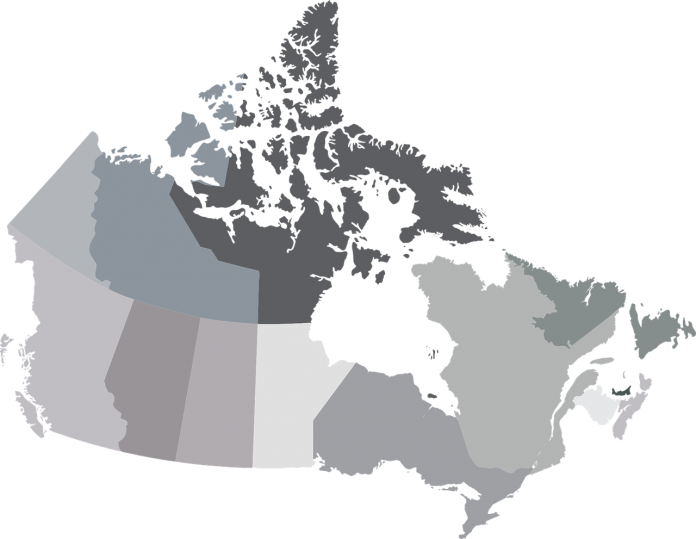

It appears Canada is already past the tipping point with debt-to-GDP expected to rise from the 2019 level of 88.3 to 131.5 per cent by 2022.

Now consider the Canadian demographic projections between now and 2068. Canadians reaching the age of 65 and older will make up between 21.4 and 29.5 per cent of the population by 2068 (compared to 18 per cent in 2020). The working population, age 15 to 64, will diminish to around 57.9 to 61.4 per cent (compared to 67 per cent in 2020).

With rising debt levels exceeding the tipping point and the future working population drastically dropping, this certainly magnifies the political elite’s position between the proverbial rock and a hard place. On the bright side, at least vaccines are on the way.

While most would agree that something had to be done, perhaps as we shelter-in-place looking forward to 2023 (the next Alberta provincial election) we will take time to seriously reflect, weigh and judge the political leadership on how they handled this crisis.

Gerard A. Lucyshyn is vice-president of research and a senior research fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

.jpg)