We must consider whether riots, unrest and ideological attacks on the very framework of Canadian society simply make the situation worse

By Jack Buckby

By Jack Buckby

Research associate

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

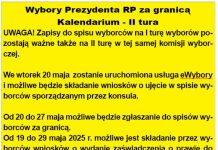

In July, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau denounced the arson and vandalism of Catholic churches across Canada in the wake of discoveries of unmarked graves at former residential schools.

After more than 1,100 unmarked graves were discovered at the sites of schools previously run by the Catholic Church in British Columbia and Saskatchewan, protests erupted. Statues of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II were torn down and churches damaged.

The sights were disturbingly similar to those seen during the Black Lives Matter riots that erupted in the United States last year. Those riots are believed to have resulted in around US$2 billion in damage.

Unlike the riots in the U.S., these protests have been denounced by the leading left-wing politicians in Canada. The fact that Trudeau would risk losing his progressive credentials by calling them out tells us two things.

First, it suggests the protests have already gone too far or are at risk of going too far. Tearing down statues and burning churches appears to be less about achieving justice for the victims – whatever justice could possibly mean for something that tragically happened so long ago. It appears to be part of a larger campaign to reshape Canadian society.

Second, it tells us politicians are both aware that these protests are going too far and willing to do something to stop them. There’s an important difference there.

In July, Eric Kaufmann argued in The Telegraph in the United Kingdom that Canada, with the exception of Quebec, is becoming the world’s first “woke nation” in the sense that “wokeness” is becoming a part of the country’s identity. These events are an example of this, and the fact that politicians are responding to it suggests it’s turning into a reality.

Riots disrupt the idea that far-left progressivism is a force for good: Trudeau likely knows this. That could be why he chose to denounce it, knowing that if he didn’t toe the fine line between acknowledging the tragedies of the past while recognizing the deep connection Canada has to its European founders, he could have been in trouble in the Sept. 20 election.

In any normal election, the Black Lives Matter riots of 2020 would have severely hurt the Democrats. But a combination of lax election integrity laws, hyper-focused mobilization of voters in key Democrat areas and the COVID-19 pandemic gave Joe Biden the edge.

It’s surely quite clear to most voters that tearing down a statue of Queen Elizabeth II makes little sense. Are we meant to believe that the Queen opposes the federal government’s promise to provide millions of dollars to help Indigenous communities find unmarked graves and investigate the circumstances of those discovered?

Unlikely.

What is the end goal of these demonstrations? What is the purpose of tearing down historic statues and burning down churches?

Given that the people negatively impacted by these actions had no involvement in the tragedies being protested, these are particularly important questions.

If it’s true that protesters want a “reckoning” of Canada’s colonial history, as British radio host Maajid Nawaz claimed in July, then we must also know what that entails. What, at this point, would be considered justice – and is it reasonably attainable?

Few would doubt the deep pain that Indigenous communities feel when these graves continue to be discovered.

But at some point, we must consider whether riots, unrest and ideological attacks on the very framework of Canadian culture and society help ease that pain or worsen it.

Jack Buckby is a research associate at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

© Troy Media

The views, opinions and positions expressed by all Troy Media columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Troy Media.

.gif)