The treatment of the non-violent trucker convoy leaders suggests a misuse of the legal system to suppress political dissent

The treatment of the non-violent trucker convoy leaders suggests a misuse of the legal system to suppress political dissent

By Gwyn Morgan

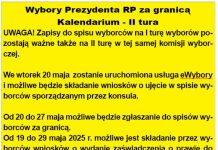

On Jan. 29, 2022, a trucker convoy headed down to the Coutts, Alta., border crossing with the U.S. to protest the COVID-19 vaccine mandates the Trudeau government had put in place. The protest turned into a full-scale blockade that lasted 17 days.

Two of the protest leaders, Chris Lysak and Jerry Morin, were arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit murder and mischief, accusations that were hard to credit given the context of the event. They remained in custody for 723 days, with Morin spending 74 of those in solitary confinement. Finally, after their lawyer filed a Charter of Rights application to examine the case, the Crown suddenly accepted a plea deal on minor firearms charges.

They were released early last month.

Contrast this with the recent case of a mother and her child fatally stabbed in a horrific random attack outside an Edmonton school. Despite a long history of violence, the accused killer had been released on bail 18 days before their murders.

In addition to the two Coutts truckers, the federal government has been persecuting Tamara Lich, who had journeyed from across the country to serve as an organizer and spokesperson for the trucker convoy protest in Ottawa that began on Jan. 29, 2022, and ended with the Trudeau government’s implementation of the Emergencies Act on Feb. 14.

Lich, an Indigenous grandmother from Alberta, was arrested and charged with “obstructing police, counselling others to commit mischief, and intimidation.” It’s hard to imagine how this petite, soft-spoken woman could “obstruct police or intimidate” anyone.

Handcuffed between two towering federal police officers, Lich was put in solitary confinement in a dungeon-like cell with a tiny window five metres above her head.

She spent two weeks in jail and was then released on bail with orders not to communicate with anyone associated with the convoy.

Later that summer, the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms selected her as the recipient of its annual “George Jonas Freedom Award for advancing and preserving freedom in our country.” At the awards ceremony in Toronto, she was photographed with another person associated with the convoy and, as a result, was re-arrested. After serving another 30 days in prison, she was again released on bail after a different judge ruled there had been “no significant interaction” with the other convoy member.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, Randal McKenzie, a habitual offender charged with weapons violations and assaulting a police officer, was set free on bail with no conditions other than periodically reporting to his parole officer. He was subsequently charged in the shooting death of Ontario Provincial Police Constable Greg Pierzchala.

The Canadian Criminal Code states: “Persons who are charged with an offence are constitutionally entitled to be released from custody unless Crown Counsel is able to justify their continued detention … including consideration of the background of the accused and risk to the public.” It’s inconceivable that Lich could be considered a risk to anyone.

The trials of Tamara Lich and convoy co-organizer Chris Barber finally began in September of last year. The federal Crown Prosecutor, presumably aware the government wanted to teach the trucker convoy protesters a lesson, had already stated he would seek a prison sentence of 10 years – a sentence given only for very serious violent assaults by habitual criminals.

The trial was originally expected to finish Oct. 15 but is taking much longer. After adjourning in December, it restarted in January, though for only one day. A shortage of available court time makes its completion date uncertain.

Tamara Lich, Chris Lysak and Jerry Morin spent a combined total of 767 days in jail – despite not having been convicted of anything. Meanwhile, Canada’s bail laws continue to allow habitually violent offenders loose after just a few days in custody.

One of the fundamental cornerstones separating a democracy from a dictatorship is the prohibition of government interference in the judicial process. But what else can explain the stark discrepancy between the Crown’s treatment of the non-violent convoy leaders and its pervasive and persistent empathy for habitual criminals and even murderers?

Even Canadians who didn’t agree with the trucker convoy’s message or methods should be concerned by the obvious disparity in their treatment at the hands of the legal system. It’s something to ponder as we await the news of yet another murder or egregious assault by a violent offender released on bail that we all know will come only too soon.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who has been a director of five global corporations.

© Troy Media

.gif)